Can a Pay-for-Performance Model Really Work in Direct Mail?

As more digitally native brands make their way up funnel and flock to direct mail, many are vying to bring a pay-for-performance pricing model along with them.

But as is the case with A/B testing, sometimes a common or even best practice in digital marketing simply does not translate to another channel. On the surface, the pay-for-performance model may seem attractive, and in certain cases it surely is, but it often proves short-sighted over time. Before weighing the pros and cons, let us review how pay-for-performance contrasts with a pay-for-service alternative, and how both pricing models will impact your bottom line.

Pay-for-performance model

In a pay-for-performance (PFP) model, the agency funds the campaign, covering data, creative, print, lettershop and postage costs. The brand then pays a premium, or commission fee, to the agency for every lead or sale generated by the program. This fee is often tied to a long-term agreement and can be rather substantial because the agency is assuming all the upfront risk.

Brands may perceive the PFP model as a lower risk approach because they will only pay for the successful generation of leads or sales. They may also consider this approach better for cash flow because there is minimal financial commitment to launch.

Pay-for-service model (the traditional approach)

Contrary to the PFP model, the brand assumes all campaign costs in the pay-for-service model. As testing proves successful and the agency optimizes for the best mix of list, offer, creative, and digital integration, the brand will financially benefit from a lower CPA and greater ROI. This is particularly true as the program scales.

Some brands may assume the pay-for-service model is a higher risk because they are making their investment in the channel prior to experiencing results. Others favor this upfront payment model because they can benefit from an optimized budget and program ROI following launch.

The bottom line

Under the PFP model, as the program scales the brand is under contract to pay the premium. This leaves the brand unable to realize all the program’s optimization and financial gains, especially over time. For example, if a brand locks into an agreement to pay $300 per sale, an agency that initially is acquiring customers for only $250 earns a $50 spread. But as performance improves (and customer acquisition costs decline), the agency’s commission may rise to, say $100, causing every sale or lead to start feeling like an expense to the brand. Instead of acquiring customers for $200, the brand is still paying $300 to the agency.

Conversely, an agency who is safely making a $50 commission is not incentivized to expand the program and take on more risk, even if the brand desires growth. In other words, the brand — who is ideally the most significant beneficiary of a successful campaign —is limiting its true growth potential.

From a cash flow perspective, most pay-for-service agencies will only require postage upfront. Then the remaining balance is due 30 days later. A successful on-going direct mail program will start to generate revenue in that time frame — perhaps as much as 70% of the eventual return — generating revenue back to the brand and minimizing financial resource concerns.

Another consideration is attribution. Today’s diverse marketing landscape has made building an attribution model a complicated process for even the most seasoned marketers. It is part art, part science, and oftentimes anything but objective. Yet that is what the PFP model requires: alignment on an objective attribution approach as payment for this model is contingent on it. Sooner or later, putting brands and agencies at odds only complicates attribution further.

Finally, the channel dynamics of direct mail are fundamentally different than digital (and affiliate) marketing, making the PFP model less realistic for direct mail agencies. With digital marketing, creative assets can be produced and published quickly, and testing insights are available within hours, requiring modest time and budgetary commitments. If a campaign is underperforming, there is an opportunity to pivot quickly or even divest altogether. This certainly makes a PFP model more reasonable for an agency to consider in digital campaigns.

Direct mail, on the other hand, is both labor intensive and carries significant material costs (data, print, lettershop, postage, etc.). And once a campaign mails, it cannot be pulled back. If the financial burden is pushed to the agency via a PFP model, they will likely aim to minimize the investment (risk) they are taking on. This means a reduced appetite for testing list, offer, creative, and digital integration; undermining the mission to develop an effective and sustainable program for the brand.

The best agencies are looking for continued growth themselves, so they are fundamentally invested in the success of their clients and their long-term finances. It is common for an agency’s business development team to qualify brands based on their readiness and fit for direct mail testing, essentially protecting them from significant risk. If the agency and brand agree the mail channel is appropriate and will be a profitable investment, the agency should recommend the traditional pay-for-service pricing model. Unlike PFP, the pay-for-service model is in the best long-term interest of the brand, and it will position both parties for continued success and growth.

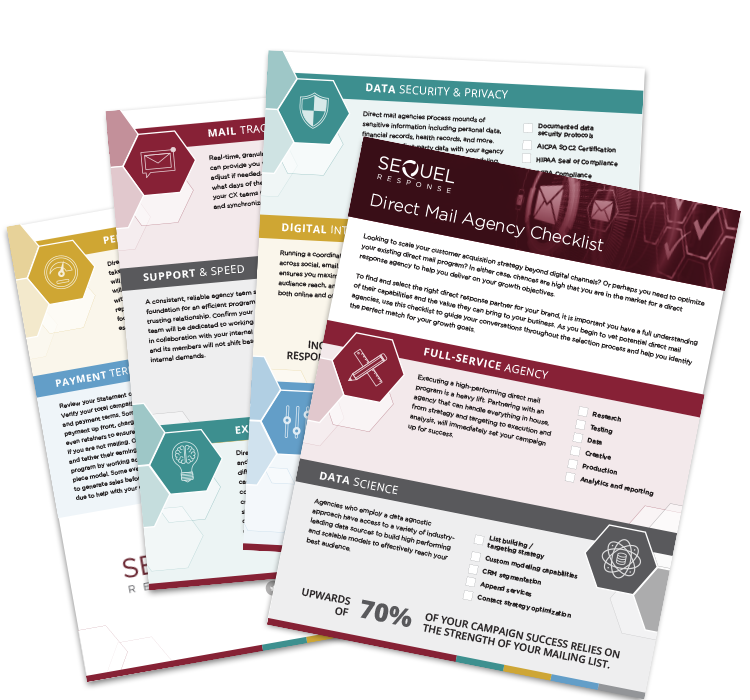

Are you looking for a direct marketing partner? Download this free checklist to ensure you ask the questions that matter most to your brand and growth goals.